By Alex Lazarus

I was recently invited to a private screening in New York of a new documentary chronicling the life and leadership philosophy of Frances Hesselbein (1915–2022), hosted by executive producer Sarah McArthur. Hesselbein, who transformed the Girl Scouts of the USA during her tenure as CEO, received the Presidential Medal of Freedom and was described by Peter Drucker as “the greatest leader” he had ever met. This unreleased documentary offers rare and moving insights into one of America’s most influential leadership thinkers. What follows are reflections from that remarkable evening.

The light falls differently in Sarah McArthur’s screening room as the documentary ends. A hushed reverence hangs in the air. For a moment, no one speaks. Then Marshall Goldsmith, coaching guru to CEOs worldwide, breaks the silence with a voice thick with emotion. “I knew her 38 years,” he says quietly. “What amazes me wasn’t the changes during those 38 years. It was the consistency. She never stopped working. She never complained.”

I find myself nodding, moved beyond words. We’ve just witnessed the life of Frances Hesselbein, a woman who, had you passed her on a Manhattan street, might have seemed unremarkable—barely five feet tall, immaculately dressed, with a signature upswept hairdo. Yet Peter Drucker, the father of modern management, called her the greatest leader he had ever encountered.

The intimate gathering around me—leadership luminaries including Goldsmith and former Ford CEO Alan Mulally—doesn’t feel like a typical film audience. They’re witnesses, collaborators, friends. For them, Frances wasn’t a subject in a documentary. She was the real thing: a revolutionary disguised as a grandmother.

The Reluctant Leader

“In Johnstown, there was this neighborhood chairman who kept pursuing me,” Frances explains in the film, her voice still carrying the lilt of Western Pennsylvania’s foothills. “Wanting me to take a Girl Scout troop. I kept saying, ‘I’m sorry, I know nothing about little girls. I’m a mother of a little boy.'”

The camera lingers on her face as she recounts how she finally relented: “One day she caught me and said, in the basement of the Second Presbyterian Church are 30 little 10-year-old Girl Scouts, Troop 17, and we’re going to have to disband the troop because they lost their leader. So, in a weak moment, I said, ‘I’ll take them.'”

Her words hang in the air—”a weak moment”—and I wonder how often history turns on such small hinges. What if Frances Hesselbein had said no that day?

Raised in a steel mill town, she had planned to “write poetry all of my life and just be quiet in the mountains of Western Pennsylvania.” Instead, she would go on to transform one of America’s largest nonprofits, advise generals at West Point, and redefine leadership for generations.

Kitchen Table Revolution

The most radical ideas often begin in the most ordinary places. For Frances, it was her kitchen table.

“With cups and saucers on my kitchen table,” she explains in the film, “I developed what I call managing in a world that’s round—circular management—where the leader is in the center, and in two concentric circles we can put a whole board, a whole staff, and we move across the organization, not up and down.”

What strikes me as I listen to McArthur describe Frances’s impact after the screening is how deceptively simple this sounds. Yet in the 1970s and 80s, when corporate America was still rigidly hierarchical, Frances was quietly dismantling power structures with her cups and saucers.

“We pitched the old hierarchical charts with everybody in little boxes,” she says, her hands moving emphatically. “Next up, down, top, bottom.”

The humor comes later, when she recalls telling her management team at Girl Scouts headquarters in New York: “I have been hearing people use ‘up’ and ‘down’ and ‘top’ and ‘bottom.’ The next time I hear ‘up, down, top, bottom,’ not only will you disappear, but your body will never be found.”

The laughter in the screening room is knowing. This petite, impeccably mannered woman was uncompromising in her vision.

“When Any Young Woman Looks in Her Handbook, She Must Be Able to Find Herself”

In the early 1980s, while corporate America was only beginning to talk about workplace diversity, Frances was already living it. The documentary reveals how she brought in designers like Halston to create fashionable uniforms, modernized the Girl Scouts’ educational materials, and, most importantly, insisted on inclusion at every level.

“A business leader who wanted to be helpful said, ‘Frances, it’s too soon to talk about diversity,'” she recounts in the film. Her response cuts through decades: “Well, it was exactly the right time. If we were going to be relevant, the organization of the future, we had to be richly representative.”

Under her leadership, the Girl Scouts tripled racial and ethnic membership at every level. One commentator in the film puts it bluntly: “She took what power and authority she did have, even as a Girl Scout troop leader in the early 1950s, and used that to help transform her community.”

After the screening, Alan Mulally leans forward to share a reflection. “What I learned from Frances was the value of serving with love and humility,” he says. “When I was thinking about joining Boeing, and later when I went to Ford, I wanted to create that same culture she embodied—where you have everybody’s heart and mind working together.”

Character Before Technique

What makes the documentary so compelling isn’t just what Frances accomplished but how she redefined leadership itself. Her most famous insight, delivered almost as an aside in the film, carries tremendous weight: “Leadership is a matter of how to be, not how to do it. It’s quality and character of the leader that determines the performance, the results.”

This philosophy found remarkable resonance in an unexpected place: the United States Military Academy at West Point. As the first civilian and first woman to hold the prestigious Class of 1951 Chair for the Study of Leadership, Frances helped develop the Army’s leadership framework: “Be, Know, Do.”

“And what that means,” explains Tom Kolditz, who worked with her at West Point, “is that the most important element of leadership is the character of the leader. Their lack of selfishness, their focus on other people, their humility. And from that comes all the other skills and abilities that a leader has.”

I’m struck by how her influence crossed boundaries that typically seem impenetrable. She moved with equal ease among Girl Scout volunteers, Fortune 500 executives, university presidents, and four-star generals. As she says in the film: “I spend a third of my time on college university campuses, a third with corporations, a third with social sector organizations, and in the middle of the third, a chunk of time with the Chief of Staff of the United States Army and his people… It’s all about leadership. It’s all about ethics. It’s all about collaboration. It’s all about transformation.”

The Final Gift: Leaving Well

Perhaps the most poignant moment in the documentary comes when Frances describes her departure from the Girl Scouts. “On January 31st, 1989, I told the national board and staff exactly one year from that day I was going to leave,” she explains. “And that last year, in a very carefully planned year of leadership transition, was the most exuberant year of my whole career. Leaving well is the last great gift a leader can give to the organization.”

As the lights come up after the screening, Sarah McArthur shares a personal story that doesn’t appear in the film. In Frances’s final years, when she was well past 100, she would still insist on regular calls with colleagues like Marshall Goldsmith and Alan Mulally. Her mental acuity remained sharp, though she spoke less than before. She would begin each call with “Hi, baby” and end with “Love you, baby.”

“That’s how she felt about everyone,” McArthur says, her voice catching slightly. “Everyone.”

The Legacy That Matters

As our small group disperses into the Manhattan evening after the screening, I find myself reflecting on what truly constitutes a legacy. Frances Hesselbein died at 107, having outlived many of her contemporaries. But what remains isn’t just institutional change or management philosophy.

What remains is how she made people feel. The documentary captures this in the faces of those who knew her—the Army general recounting how she insisted on walking Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg despite her age, the young woman from Harlem who felt truly seen by Frances, the driver who misses her daily conversations.

One viewer at our screening puts it perfectly:

“I think we just witnessed a masterclass on leadership because it’s a masterclass on character.”

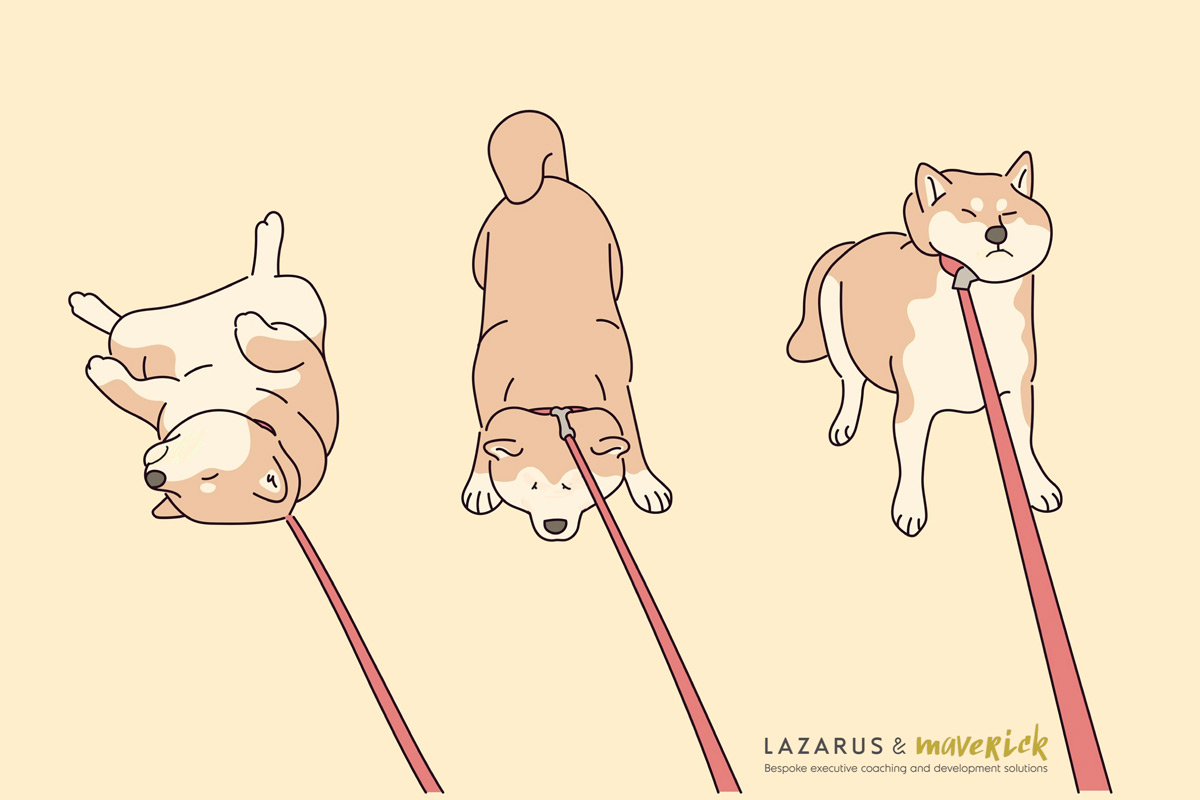

Frances understood something fundamental about leadership that we often forget in our technique-obsessed age: leadership isn’t primarily about what you do. It’s about who you are. It’s not about rising to the top; it’s about drawing circles that include others. It’s not about asserting power; it’s about releasing potential.

As one of her colleagues says in the film’s closing moments: “There are different ways to be a torch-bearer.” In carrying Frances Hesselbein’s flame forward, perhaps our task isn’t to imitate her methods but to embody her essence—to lead not from position but from character, to speak with precision but listen with compassion, to move across rather than up and down, and to remember always that, in her words, “to serve is to live.”